I'm staying!

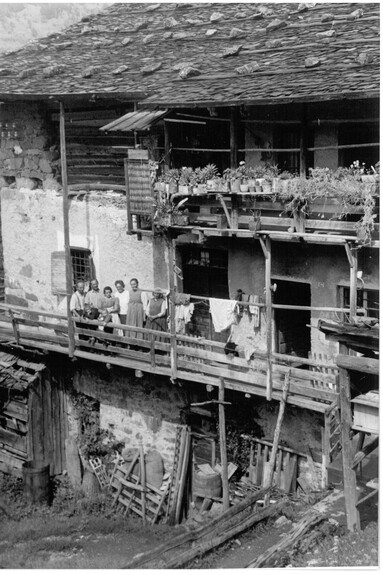

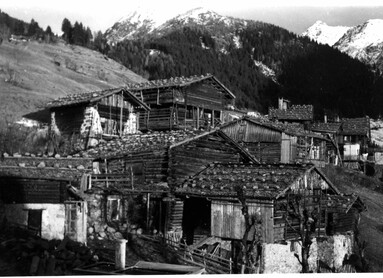

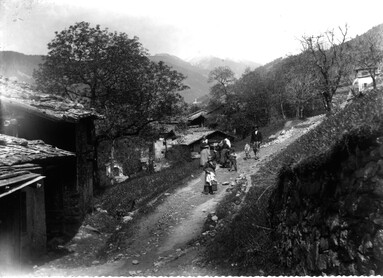

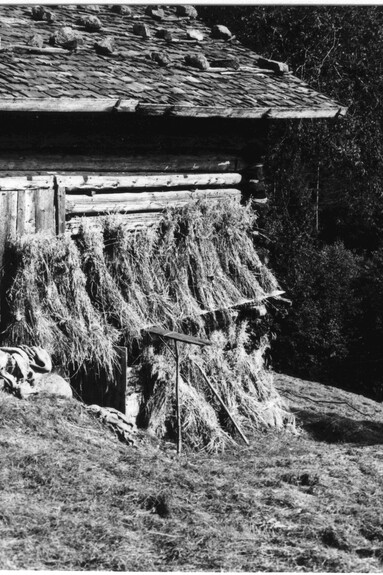

The ‘maso’ (mountain farmstead), a landmark in the Mòcheni Valley

People say that being stubborn is a fault. Old Uncle Jacopo clearly didn't think so, otherwise he would have changed his life long ago. He would have moved to a big city, Milan or Turin, to work as a labourer with a fixed monthly salary and paid sick leave and would have gone home to sleep in a modern house, one with central heating.

Instead, he decided to stay. To extract land from the mountain, one stone at a time and to transform those steep, wooded slopes into arable fields. With the leftover stones, he built embankments that also served as boundaries for what was his.

That day, too, he woke up before dawn and looked at the sky. The first thing he did every day. A frugal breakfast and then out into the frost-covered fields.

His hands were frozen, the plough struggled to advance in the hard earth. He had asked himself many times why he had decided to stay. Was he stubborn? Perhaps. But there was something deeper, something even he could not explain.

That day, the question was overwhelming. The shingles on the roof were in danger of rotting and needed to be replaced. One by one. A chore he had put off for too long.

The ‘maso’ is unforgiving. It is a jealous lover. It needs care. Constant attention. It does not allow for holidays, it does not understand if you are sick or simply tired. It has no mercy.

But it is always there. Ready to protect you and give you the warmth of the hearth while it snows outside.

This is what he thought about as he worked the cheese in the dairy. A small wooden room on his property, because in the Mòcheni Valley there were no communal dairies where milk could be taken to, so each farm had its own dairy.

And he couldn't stop thinking about why he had decided to stay and whether it had been the right choice. The villagers who had left were returning to the village in their white Fiat 600s and warm coats. They boasted of having made their fortune.

He, on the other hand, had stayed behind to be a farmer. Stubborn as a mule.

Hertkopfet.*

He left the bucket in the toll booth and headed for the farmhouse door, while outside it was already dark.

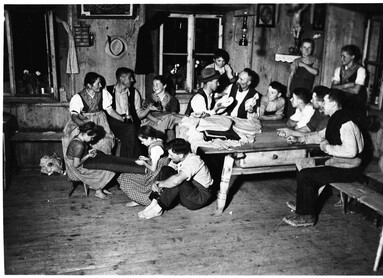

Inside, his wife and three children, still too young to help in the fields, were waiting for him. Later, his younger brother Tommaso would join them with his wife and children. They had gone down to Pergine for the market**.

Then they would all have dinner together around the same hearth.

Finally, he understood why he had decided to stay.

He had to take care of the farm. It was the family's anchor. It held together everything that really mattered. ***

* A word in the Mòcheno language meaning "stubborn."

**In the Mòcheni Valley, the "closed farm" rule did not exist. The farm, therefore, was not inherited solely by the firstborn son but was divided among the male members of the family. Each of them received a portion of the property, where he lived alone or with the family he had formed. Thus, over time, other dwellings were added to the main house, giving rise to small clusters scattered across the territory that still characterize the landscape today.

*** 'Maso' comes from the Latin 'mansum' or 'mansus', the past participle of manēre = 'to stay, to remain'